My two cents on AI for battery science

Published:

Recently I got a chance to review what research topics I have been looking at in the field of AI for battery science in the past a few years. I would like to share it here, intending to attracting more discussions and potential collaborators. I expect to update the contents frequently.

Disclaimer: views are my own (i.e., this blog post does not express the views or opinions of my employer or organization). My personal views are inevitably biased.

Firstly, for a general understanding of AI4S, a recent survey is comprehensive.

AI is mainly useful for two aspects: molecular/materials design, and battery management system

1. Closed-loop DMTA

Overall, the goal of the battery industry wants to achieve is similar to AI in pharmaceuticals, that is, to implement a closed-loop DMTA process. “D” stands for design (molecular design), “M” for make (molecular synthesis), “T” for test (property test, dry experiments on computers or wet-lab experiments), and “A” for analysis (i.e., how to achieve automatic feedback and improvement of the closed-loop process). A representative work is 2023 Koscher Science Autonomous. Thus, role of AI in battery science should be to improve each of the four DMTA stages.

1.1 Machine Learning Potential (MLP)

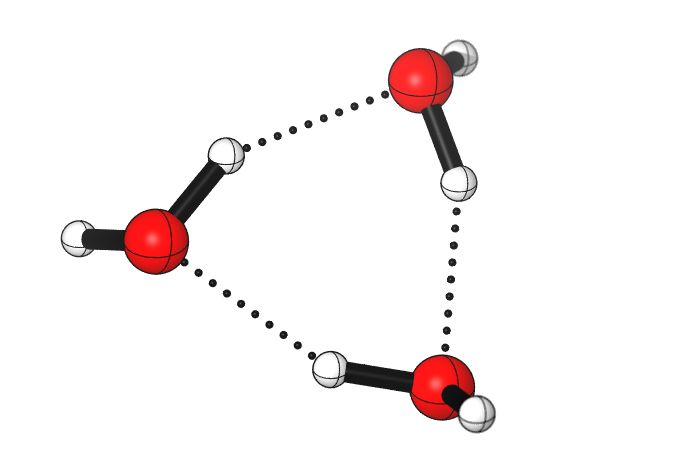

MLP refers to the use of ML/DL to fit the interactions between atoms in a physical system. Traditional physical methods are mainly quantum mechanics (QM) and molecular mechanics (MM). The problem with QM is its high algorithmic complexity, making it difficult to apply to large systems with more than 1000 atoms and simulations at the ns timescale, which are often needed in battery research. The issue with MM is its inaccuracy and difficulty in optimization. MLP is expected to solve this problem by using QM labelled data as training data and training a surrogate model with DL to accurately and efficiently describe the interactions between atoms. Given the atomic coordinates $X$ and atomic types $z$ of a physical system, we train a model $M(\theta)$ to predict the forces $F$ and energies $E$ of each atom. With force and energy, we theoretically can obtain all properties of the physical system. A survey on this direction can refer to the 2021 Unke CR Machine.

NequIP and MACE are currently considered the state-of-the-art (SOTA) models for MLP, both developed based on equivariant graph neural networks (EGNN). Another model is DeepMD, which also performs well, with the development team being DP Technology (possibly the most professional and comprehensive team in China doing AI4S) and AISI, with many domestic users in China. Recently, Samsung published a benchmark article evaluating the performance of various mainstream models in semiconductor materials, see 2023 Kim NeurIPS Benchmarking, which is also instructive for battery material research.

From an AI or mathematical perspective, the task is to incorporate equivariant models, which has been a hot topic in recent years. However, progress in this direction seems to have slowed down recently, but there is still some work emerging, such as the 2024 Luo ICLR Enabling, suitable for researchers familiar with group theory.

From a physics perspective, the task is how to incorporate key physical information into the black-box DL model to make the model physical meaningful (in fact, equivariance can also be seen as a physical property). The current focus is on long-range interactions and spin-orbit coupling (SOC). The former is important for the simulation of battery interfaces, electrolytes, and other systems, with some recent work emerging, such as DPLR andSCFNN. SOC is important for transition metals, such as Ni and Co in NCM cathode materials in battery systems, with representative work by Hongjun Xiang from Fudan and Yong Xu from Tsinghua (see 2022 Yu PRB Complex and 2023 Gong NC General). This direction is suitable for those with a background in theoretical chemistry or condensed matter physics.

In specific battery applications, several aspects are particularly important:

Short-to-long extrapolation: In batteries, the focus is often on long timescale scientific problems, such as the formation of the solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI), the calculation of diffusion coefficient, and ionic conductivity, requiring simulations usually >= 10 ns. How to use short trajectories to obtain long trajectories is crucial. Two representative works in this area are the 2022 Xie NC Acclerating, which centers on multi-task training, and the 2023 Fu TMLR Simulate, which is based on diffusion models.

Stability & Sampling: Stability is an issue often overlooked in MLP research. Everyone (especially in the AI community) likes to compete on fixed metrics, such as force and energy errors and few-shot learning, etc. However, the actual MD application should be the only standard for testing the quality of MLP. A significant work in this direction is the 2022 Fu arXiv Forces, and DiffMD is also relevant, with this blog post explaining it well. These works highlight the importance of stability in GNN based dynamics, especially when trying reproducing molecular dynamics without force information. On the other hand, how to efficiently sample training data for MLP is another important issue, with significant works including active learning-based sampling, e.g., DP-GEN, learning from mistakes, e.g., the 2023 Magar CMS Learning. We also discussed this issue in more detail and depth in our recent SIS-MLPMD work.

Multiscale Simulation: Multiscale simulation has always been a key issue in computational chemistry or more generally scientific computing. The 2013 Nobel Prize in Chemistry is a representative example. The battery system is a standard multiscale model system, with different scientific problems suitable for different theoretical methods. So how to use AI to bridge different scale simulations is a key issue. An example is from QM to MLP to MD, and another is from QM to MLP to multiphysics simulation. In addition, there are studies showing how to apply multiscale (or multi-fidelity) data and automatically optimizing force fields, with representative works including DMFF, JAX-ReaxFF, and our recent 2024 JPCL paper.

Foundation Model: The recent hot topic in MLP is the foundation model of course, with representative works being DPA-2 and MACE-MP-0. However, in the realm of batteries, I believe that in the future, there will be corresponding “small models” specifically for batteries to cover the simulation needs of various conditions (different temperatures, concentrations, pressures) and systems (solid-state electrolytes, liquid electrolytes, interfaces, bulk). Here, it is crucial to design efficient framework and multi-task learning.

Unified modeling of 2D topology and 3D geometry information, e.g., see 2023 Zhang CS An One example combining LLM with GNN is 2023 Soares arXiv Improving。Attention mechanism is often useful in dealing with key features of moelcular graph, e.g., 2023 Zhang Bioinformatics Molecular, such methods enable model to learn key information of important functional groups that is related with electrochemical properties such as redox potential.

1.2 Molecular and Material Generation

The D (esign) mentioned at the beginning of the article corresponds to molecular and material generation, that is, designing the composition and structure of molecules and materials based on target properties. The popularity of deep generative models has brought many related work to AI conferences, but most are currently focused on drug and protein applications, with fewer applications in batteries and other materials. The main issue is that the current mainstream molecular databases (such as zinc, GDB-13) and PDB are similar to drug molecules and proteins, which are often quite different from battery materials. From an AI perspective, the question is how to solve the domain-adaptation problem, and from a scientific perspective, it is how to find or construct a basic dataset for battery-related molecular and material generation.

A natural choice is the Materials Project (MP). A work based on MP is Google’s recent GNoME, which is a very straightforward approach based on NequIP and MP for element substitution. Another work is Microsoft’s MatterGen.

The Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) is the core issue of batteries, and how to regulate the structure and composition of the SEI through electrolyte operation is a key issue in battery chemistry, such as the number, distance, and symmetry of F atoms in lithium salts. MatterGen incorporates symmetry into the score network when applying diffusion models. Following this approach, we can also introduce more constraints (such as the quantity of F atoms) when applying diffusion models.

If we don not want using MP directly, we need to develop our databases. Starting from organic small molecules in electrolytes is relatively simple. A representative work in this area is the 2023 Gao JACS Data.

Another challenge is to generate stable conformation of molecules, the SOTA model in this aspect is Torsional Diffusion,this model is novel in focusing on the main factor of conformation generation, i.e., torsional angle,which accelerates the generation process compared with atomwise generation.

1.3 Retrosynthesis, Synthesizability, and Automated Laboratories

The M (ake) in DMTA involves research on retrosynthesis, synthesizability, and automated laboratories. Again, in these three aspects, the AI pharmaceutical industry is a pioneer, and the materials field is a step behind.

Retrosynthesis is the task of automatically generating synthesis routes for target molecules/materials. Current research is mostly limited to organic small molecules. Synthesizability refers to predicting the likelihood of successfully synthesizing target molecules, with AI pharmaceuticals generally using metrics like SAScore. Recent work in the battery materials field can refer to the 2021 Ouyang NC Synthetic paper.

Automated laboratories refer to how to apply robots to automatically perform related chemical experiments in chemical laboratories. This direction involves many factors, and points that AI background individuals can be involved in include literature information extraction and generation, robot control, object detection, etc. Related works can refer to the 2023 Ha SA AI-driven paper.

1.4 Other

Within the DMTA framework, there are other important factors.

1.4.1

The first is how to ensure that each round of feedback is effectively given to the model to achieve long-term model improvement. This issue involves the processing of new data, or the problem of online learning, as well as reinforcement learning, i.e., how to design rewards and update policies in the closed-loop of DMTA, and how to balance exploration and exploitation.

1.4.2

The second issue is whether the entire DMTA framework can be made end-to-end differentiable, which I think may be difficult to achieve, but there are some related works trying to make RDF and other molecular simulation properties differentiable, such as 2023 Wang JCP Learning, 2022 Axelord AMR Learning.

Why end-to-end differentiable is expected? In battery research, there are many main properties of interest, e.g., diffusion coefficient (D) and conductivity (C), which determine the fast-charging performance of batteries. However, obtaining these two properties accurately and efficiently lacks effective means.

Experimental errors mainly arise from the fact that different experimental methods are often used in different papers, leading to an inability to perform even qualitative fair comparisons of D and C obtained by different experimental methods. You can realize the issue by playing and plot with the LionDB database.

The main means of obtaining D and C computationally is through molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, where trajectories sampled by MD are used to calculate the mean squared displacement (MSD) of the relevant atoms (such as Li+), from which D and then C are calculated. The errors of this method mainly come from two aspects. First, insufficient sampling due to simulations not being long enough (e.g., AIMD can only run simulations at the ps level, but some electrolytes require simulations >50 ns). Therefore, it is crucial to use short trajectories to infer long trajectories, this is the “short-to-long extrapolation” we discussed above. The second aspect is the lack of accuracy in the underlying potential (whether it is a traditional force field or a machine learning potential).

So, is there a method that can achieve the entire process from molecular structure to GNN potential to D/C end-to-end differentiable? We assume that we have a sufficient amount of experimental data for D/C, and these data are all obtained using the same experimental method, i.e., a larger and more accurate LionDB. Then, this data can be used to train this framework and attempt to extrapolate to unseen electrolyte systems. Below are some relevant works:

- RDF differentiable simulation: 2023 Wang JCP Learning

- DiffTre and its follow-up work

- TorchMD

1.4.3

The third is how to apply LLM to chemical or more specifically battery research. There is already related work for battery electrolyte molecule generation (e.g., the 2023 Lei arXiv A paper) and formula design (e.g., the 2023 Soares pre-print Capturing paper) and corresponding multimodal representations. GNN can only cover molecular structure while lacks the information of temperature, concentration, additives, etc, this case makes it crucial to proper deal with multimodal information in batteries.

2. BMS

In addition to molecular/material research related to batteries, the field of battery management systems (BMS) is also an application area for DL. Traditional BMS algorithms such as electrochemical models, equivalent circuit models, and Kalman filtering algorithms are increasingly combined with DL, such as 2023 Tian ESM Deep, 2022 Su TTE A, 2024 Li GEIT An.